Climate Grief in the Everglades

"It's not dying. It's morphing. It's morphing into something that is so different from what you fell in love with."

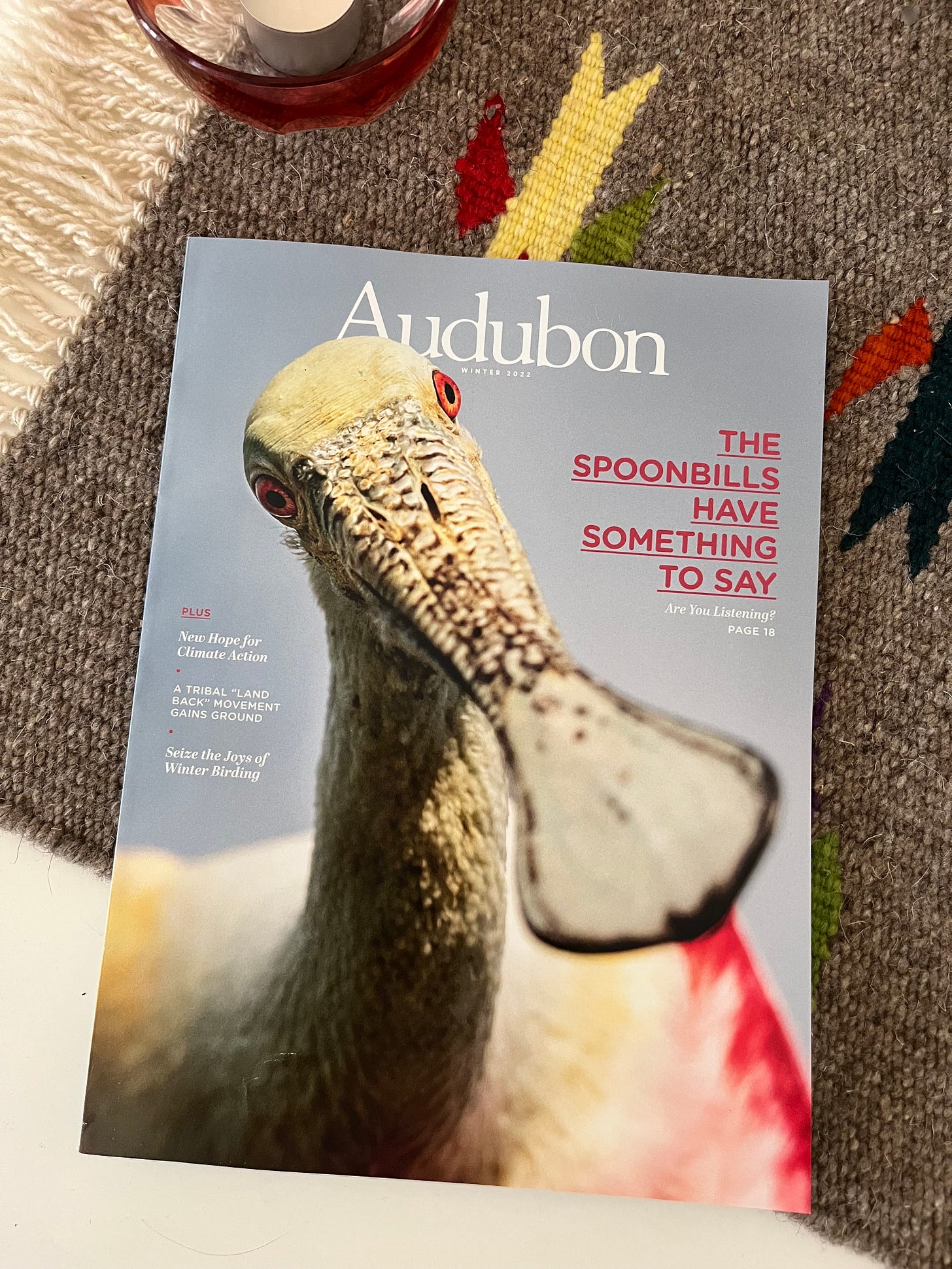

Last week a story I’ve been working on all year published online, and I didn’t tell anybody. It’s the Audubon winter cover story, which is about climate change in the Everglades, how it’s altered the ecology of Florida Bay, and how scientists down there have changed the way they approach conservation given that things will never be the same again—told through the lens of a goofy pink bird called the Roseate Spoonbill.

I had coffee with a friend yesterday and admitted that the story was out and yet I hadn’t really shared it, that I knew I needed to put it in the newsletter and tweet it out, etc. But I couldn’t bring myself to do it. The project fully absorbed six months of my year. I poured so much into it, it means so much to me, and so I can’t show it to anyone. My private obsession is now being mailed to hundreds of thousands of people! “It’s too vulnerable,” she agreed. So here I am, starting out my Thursday morning by getting vulnerable, I guess. A writer’s life: Gutting myself in public and asking everyone to look at my entrails.

Here’s the link. The print edition will hit mailboxes in the next couple of weeks.

The main character, outside of the Everglades itself and the spoonbills, is Jerry Lorenz, who’s been studying the birds and the ecosystem since 1989, and has personally watched and been extremely confused as sea levels rose into his study system over the past decade and threw the whole thing of out of whack. I love hanging out with longtime field ecologists like Jerry and I’m lucky to have done a lot of it. They are so knowledgable, and talking to them is like stepping into another dimension where the only thing that exists is their species, their study site, their open questions, and their model for how their ecosystem works.

My favorite ecology elders are in love. I mean that word in a pure sense. They want to know their object(s) of study without changing them, to support them, to celebrate them. Only love can explain the utter devotion and drive, day in and day out for years or a lifetime, to understand something so complicated and ultimately unknowable. What Jerry loves is Florida Bay, and the spoonbills as its representatives.

And so what Jerry is feeling now is grief, the flipside of love. He still loves something that is in many ways already gone. The place has changed. The birds he spent his career studying have abandoned him—they have left Florida Bay, where he built his life, and now live farther north, deeper into the Everglades and are experimenting with nesting outside of the state. He visits the places that in his memory are teeming with spoonbills—and they are eerily silent. There is tremendous loss in his story, and in his retelling of it. He wraps himself up in the science, focusing on understanding what has changed and how, to avoid looking at and feeling his grief. I can relate.

One afternoon I got him to acknowledge his grief for a brief moment. We had already spent something like four hours in his office as I asked him a million questions and he showed me maps and data and talked me through a career’s worth of research. Close to the end of the conversation I asked him what it meant for him emotionally. What was it like for him as a person to have witnessed these changes:

When I was a younger scientist I heard older scientists say, ‘It's when you prove yourself wrong that you're most excited.’ And I thought, no, that is not true. But it is. Because it leads you down a different path. When I could finally start to explain why these birds weren't doing what I expected them to do, that was marvelous. So from a scientific perspective, it's like, ‘Oh, that is way cool.’

Then you start chasing that from an emotional, environmental, conservation point of view. It's sad and scary is what it is. What happens to my birds now? What happens to my bay? If it wasn’t for that giant piece of real estate I would not be here. And you're watching it. It's not dying. It's morphing. It's morphing into something that is so different from what you fell in love with. And that is very disheartening.

Then he looked at me like I had shot him. And we went back to the science.

Earlier in my career I worked with coral reef biologist Nancy Knowlton, another elder ecologist. In the 1970s she started studying Caribbean coral reefs—first trying to understand them and then watching them collapse as pollution from resorts killed corals and depleted their wildlife. She spoke often of her career, and the current work of ecologists, as “writing ever-more detailed obituaries” of ecosystems. We get into the field because we’re fascinated by the puzzle of life, understanding how organisms coexist and interact and influence one another, and because we want to support their continuance. But in many places ecosystems are unraveling. We are watching them come apart, recording their demise, and finding that the main way to help them is to challenge globe-spanning systems of trade and capital and development, colonialism and extraction, that are so entrenched that they can seem divinely ordained.

Nancy’s response to her career writing obituaries for the ocean was to champion what she called Ocean Optimism, which evolved into the Smithsonian’s Earth Optimism initiative. Her goal was to elevate stories of conservation successes and devote intentional time to describing what we can do to support ecosystems and wildlife—what has been proven to work to restore populations and landscapes. It was an important project for my career in that it rooted me in place. Most of the successes we highlighted were local, hands-on projects. Every ecosystem is different and requires a different response, I learned; there are no blanket solutions.

Solutions journalism is important and we need to talk about successes and study them. (Of course!) But when I look back at that optimism project I also see a kind of avoidance. The grief is too hard, it’s too painful to admit that we have missed our chance to study a healthy Caribbean coral reef. We are in disbelief that it’s already gone. We can’t stop talking about what it used to be like. So we focus on some successes to make ourselves feel better, a kind of scientific emotional regulation to avoid inevitable pain.

I find avoidance in my work, too. Like Jerry I find climate change fascinating in a sick way, in that sometimes the best way to understand a system is to take it apart. And that is what we are doing right now across the globe—we are learning how things used to work by watching them collapse. Cataloguing the precise way Roseate Spoonbills abandoned Florida Bay confirmed some of Jerry’s theories about how the complex ecosystem was able to support them in the first place. There is something exciting about that, and it is certainly information that could be used to support them elsewhere. But, again, it’s also a way of distracting ourselves from the pain of loss.

As I’ve gotten older I’ve come to value the act of witnessing, of being a witness and having one. I’ve carried enough grief by now to know that there is little anyone can do to help me with that load—and little I can do to relieve loved ones of theirs. I can clean their kitchen or make a meal, I can answer the phone and listen to their stories and remind them I love them. But ultimately our grief belongs to us. (“I can’t carry it for you, but I can carry you.” -Samwise Gamgee)

I’ve learned that what I need, and what many of us need, is to have a witness and to bear witness. To be brave enough to sit through the hard feelings and say—that really sucks, I see you, I wish it were different, you’re not alone, I’ll be with you through this.

That is what Jerry is doing with Florida Bay, and what Nancy did with her coral reefs. They are witnesses. I feel honored that my job as a science journalist is to know them and to help tell their stories—to be their witnesses, to communicate what they’ve witnessed, and to let us all be witnesses to our changing Earth. Like Nancy and Jerry, it wasn’t the job I signed up for. None of us signed up to live through times like these. But here we all are.

Warmly Yours,

Hannah

What I’m reading

NOAA published its 2022 Arctic Report Card. The verdict: The region is continuing to warm and thaw. 2022 was the sixth warmest year since 1990.

An update from Utqiaġvik, which set a high temperature record this December. (Previous Utqiaġvik coverage on Warm Feelings)

Imagining a green Antarctica. “Between now and the end of the century, thousands of square kilometres of permanently ice-free habitat is going to open up on the continent, even under moderate climate change.”

Americans continue to move into disaster zones. Rachel Ramirez at CNN: “Researchers found an alarming upward trend of people flocking to the wildfire-prone and drought-stricken West, where states are facing unprecedented water shortages . . . [C]oastal areas that are at high risk to the most destructive storms, like the coasts of Florida and Texas, remain key migration hot spots.” Denial is a powerful drug.

FEMA’s flood maps are woefully out of date. “Climate has changed so much that the maps aren’t going to keep up for some time,” said W. Craig Fugate, FEMA administrator under President Barack Obama. “They are not designed for extreme rainfall events.”

Carbon credit exploitation. “The current lack of regulation and clear rules has given rise to carbon cowboys—brokers who have descended on Indigenous communities in Honduras, Brazil and Colombia and talked them into signing away their rights to the carbon in their forests, and in turn the payments that can come with them.”

What I’m listening to. My favorite music that came out this year: Tallies’ Patina (Heaven’s Touch), Beyonce’s Renaissance (Virgo’s Groove), Alvvays’ Blue Rev (After the Earthquake), Nilüfer Yanya’s Painless (Midnight Sun), Jazmine Sullivan’s Heaux Tales, Mo’ Tales (I can’t get enough heaux tales) (BPW), Mitski’s Laurel Hell (Working for the Knife), and Jockstrap’s I Love You Jennifer B (Glasgow). But it’s sparkly season now which means I can continue to make the case for this song being a holiday classic:

Thanks for reading! If you liked this, forward it or post it on the collapsing star Twitter or otherwise share it with a friend or colleague or frenemy if you want.