Mailbag

Thanks for the kind messages about the first edition of Warm Feelings. Apparently having phantom climate change feelings on Halloween was a widespread phenomenon. There is a collective consciousness after all!

Several readers offered additional explanations for why Halloween might have actually felt colder to us when we were kids. Your mileage may vary:

We were physically smaller. Smaller objects cool down more quickly than large ones (think of a small cup of coffee versus a big one).

We were wearing cheap costumes made of thin materials (likely made of fossil fuels such as polyester, spandex, and nylon), accelerating our cooldown.

Overprotective parents forced us to wear jackets.

Everything felt new and exciting, we were young and knew nothing of life, every experience was novel and terrifying, and so we shivered.

Which End of the Elephant Are You Holding?

A story from my reporting cutting-room floor

Above the Arctic Circle sits the northernmost city in the United States: Utqiaġvik, Alaska. It’s home to roughly 4,500 people (the 12th largest city in Alaska) as well as one of the world’s most important climate science outposts. In 2017 I went there to see the impacts of a warming Arctic, a trip that fundamentally changed my outlook on and understanding of climate change.

Utqiaġvik is an Iñupiat town where Indigenous Alaskans have lived off the land for at least 1,500 years, hunting whale, caribou, eider ducks, fish, and seals and gathering berries and roots. Over the past 150 years colonial forces—military, science, and fossil fuels—have moved in. In 1881 the U.S. Army Signal Corps and the Smithsonian set up a weather station in what was then called Barrow (the city was formally returned its Iñupiaq name Utqiaġvik in 2016). To sight Japanese attacks during World War II, the military installed a radar station, which was expanded during the Cold War to scout for signs of Russian invaders over the North Pole. Utqiaġvik continued to be used as a military base in later warfare: I was there to write a story for Audubon about seabirds living under munitions boxes discarded during the Korean War.

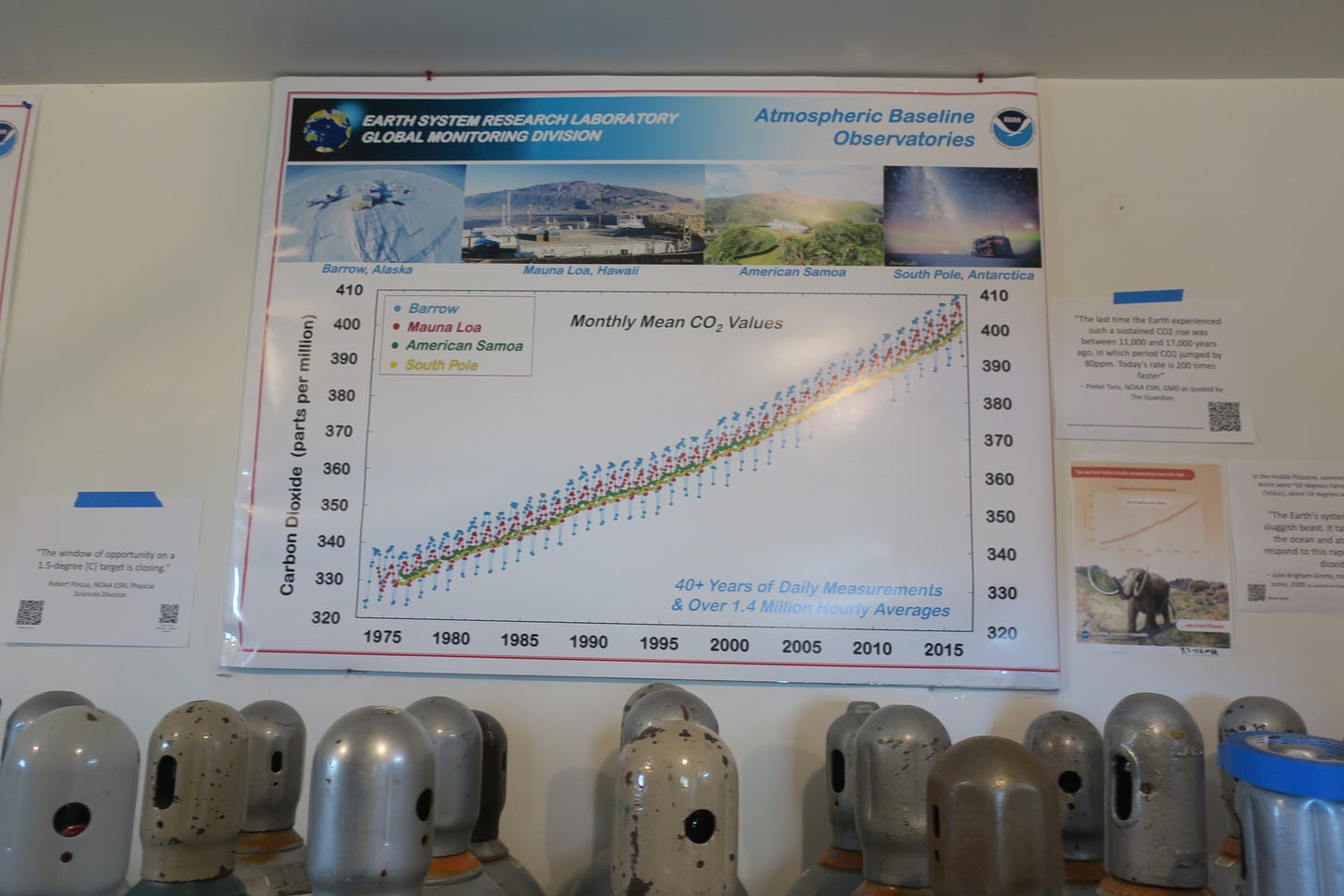

Utqiaġvik is also the site of the one of the world’s longest-running atmospheric datasets. In 1971 NOAA took its first carbon dioxide sample there, and in 1973 established a permanent laboratory. The Barrow Atmospheric Baseline Observatory’s list of sampled gases is immense (carbon dioxide, methane, HFCs, and dozens more) and matched or beat by only three other Global Monitoring baseline laboratories: Hawaii’s Mauna Loa (home to the Keeling Curve), the South Pole, and Samoa. Its samples are considered pure air, free from the kind of human influence and chemical emissions that would muddy a dataset practically anywhere else in the world, because of its location: At the very northern tip of Alaska, it receives well-mixed Arctic winds off the Beaufort Sea.

After five days camping with black guillemots on a sandbar, I returned to civilization in Utqiaġvik, where I had a few days with little to do but poke around and chat with locals. Many folks were eager to talk about climate change. I heard stories about freezers dug into permafrost that had thawed, spoiling food supplies. One Iñupiat fisherman described the shift in salmon species over 40 years: “We used to get chum salmon, then about 20 years ago we got king salmon. Now we get reds. The water is getting warmer.” Others bemoaned the loss of protective sea ice; in its absence bigger waves strike land, washing out roads and runways, tearing away the shoreline, and forcing people to relocate their homes—and possibly, in the future, entire towns.

“We need to move Barrow. We need to move Wainwright. Point Hope needs to be moved again,” said Mike Aamodt, former North Slope Borough Assembly President. “It’s changing up here. We don’t have that ice protection anymore. What can we do?”

By then I had been working on climate change for about nine years in some capacity, and in all that time not a single person had been able to give me a unifying theory of Earth’s climate—how wind circulation patterns and ocean currents intersect with our carbon emissions. I felt driven to understand how the whole thing worked, perhaps seeking some certainty. If anyone could explain it, I figured, it had to be the scientists who manage Utqiaġvik’s NOAA laboratory—sitting at the top of the world, with their pure air samples and connections to a global network of climate observatories. So, I got in touch with station chief Bryan Thomas to ask him how the planet works.

On August 12, 2017, Thomas drove me and photographer Peter Mather (who did not take these photos) in his pick-up to his workplace. We followed boardwalk trails in the drizzle while he pointed out instruments visible on the tundra—an eddy covariance flux tower to measure methane, an albedo rack to measure surface reflectiveness, a GPS antenna (part of the Plate Boundary Observatory network).

He led us into the observatory: a series of trailers on stilts (placed directly on the tundra they would melt the permafrost and collapse the ground below) that held a small office space, racks of computers, and machines for collecting and analyzing air samples. The center of the operation was a set of glass flasks, the same used at climate observatories around the world. “It’s dumb simple technology,” Thomas said.

“It’s just a glass flask.” An automated machine takes regular air samples—opening an evacuated flask fills it with air—which then are mailed to the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego for analysis.

“This is not something that we’re just doing here. They’re doing this in Africa. They’re doing this it in the middle of the Pacific Ocean on container ships. They’re doing it in the atmosphere with little planes. They’re doing it all over the place,” he said. “All of those flasks are telling us that change is happening. This is not something that’s easy to get wrong. This is very easy to get right, and that’s the point of it, is that it’s really simple. It’s a pump and a battery and a flask.”

As he led us through the facility, I peppered him with questions about currents and air circulation, Hadley cells and ocean oscillations, all attempts to prompt him to put all the pieces together into one big picture of the global climate.

Somewhat puzzled, he listed examples of how the air and sea and energy interact. Sea ice reflects heat; the ocean absorbs it. Less sea ice means there is more energy in the water, and that water is more mobile, so waves strike harder onto the shore. Stronger storms, generated by warmer, water-rich air, erode soil and permafrost which releases methane and carbon dioxide. A warmer atmosphere melts glaciers, which raises sea levels. “It’s all connected,” he said.

I remained unsatisfied. That was a list of processes! I demanded a holistic description, a linear narrative to explain how it’s all connected. How do air and ocean currents interact globally, and how does carbon dioxide alter those patterns?

I may as well have asked him to explain the gods.

“Everybody sees it differently,” Thomas patiently told me. “If you’re looking at the elephant and you have a hold of the tail, you know you have the hold of the tail of the elephant. But if you’re looking at the trunk of the elephant, you only know you have a hold of the trunk. You don’t know it’s an elephant because you’re not talking together.”

“What I have a hold on at the station is the air,” he continued. “And I can tell you that the air is getting warmer.”

Up until that point I believed, perhaps naively, that there was someone out there who understood how this all worked. That there were people who fully understood the climate, who could predict how it would change and how those changes would affect us. I thought, or hoped, that someone was in charge who could tell us how to fix this.

But it turns out that no one can see the whole elephant.

I learned that day that climate change is the world’s biggest group project. The climate is mysterious, its forces and activities mystical. Its global movements have hyperlocal effects. It exists on a scale that the human mind has not evolved to perceive, to grasp, to predict. Explaining the climate is one reason why humanity has religion. It is beyond us. That’s why the world’s climate scientists have to get together on a regular basis to compare notes, to build computer models with the best data they have (which is always getting better). And it’s why it’s truly evil that many corporations, government leaders, intellectuals, and others are invested in muddying the waters of our best knowledge with disinformation, with climate denial, with false science and willfully incorrect interpretations. This is a hard enough group project as it is. Stop poisoning it!

The metaphor of the elephant, holding the tail or the trunk, has stuck with me over the years (and why I find myself compelled to tell it now). I find a strange solace in it. If Thomas can’t fully understand the climate, that lets me off the hook. And if I can accept that the details of our climate future are ultimately unknowable, given we can’t describe fully the climate present, then my mind is freed up to focus on what is in front of me—what is happening now, what I know to be true, and what I can do about it today. I can look at my part of the elephant.

This goes beyond science. We are each holding a part of the elephant. Whether you start now, or wait a decade, I guarantee that soon you will be looking at climate change, if you aren’t already. (It can be hard to see sometimes.) Which means you will have an opportunity to do something about it. Maybe there is something that you can do right now to contribute to the group project—to describe what’s happening in your communities and the places you know, or what you suspect will happen soon, and then try to start addressing it, even in a small way.

Some scary feelings about climate change come from a sense of helplessness, that there is nothing we can do. Because there is no quick fix, no one thing to do, and no one to tell you how to do it. No one knows what is going to happen, certainly not me.

I find comfort, too, in this—that each of us must find our own way forward. We will travel through the changes together. But we have to accept that there is no one coming to save us. We are going to have to save ourselves.

Warmly yours,

Hannah

What I’m reading

Liz Weil walks through ideas of leading climate philosophers and activists (Andreas Malm, Mary Heglar, Timothy Morton) in NYMag’s Intelligencer as she tries to figure out how to live through apocalypse. “Yes, it’s a catastrophe. We need to catastrophize. And no, you would not be better off if you continued to tell yourself otherwise.” I am not sure I totally agree but it’s a thought-provoking and entertaining read. (I’ll deal with the subject of apocalypse in future editions.)

Friend of the newsletter Pedro Hernández published a report that connects the biodiversity crisis, nature access crisis (environmental justice), and climate crisis with a super clear narrative and analysis. Everyone working in conservation should read it.

Meet some climate activists: Bill McKibben introduces friends from the COP27 protest in his Substack.

Two countries with opposite approaches: Colombia President Gustavo Petro wants to break his country’s reliance on fossil fuel revenue by phasing out oil and taxing coal miners. Meanwhile Guyana gave petrostate Exxon a sweet deal to drill for oil, claiming proceeds will fund climate adaptation efforts.

What I’m listening to: The new Weyes Blood album on loop while bundled up and stalking sidewalks in this cold sparkly city.

And let me know! Email me warmfeelings@substack.com. Tell me all your secrets. Did the elephant story resonate with you?